February 15, 2020

by Bruce Schneier

Fellow and Lecturer, Harvard Kennedy School

schneier@schneier.com

https://www.schneier.com

A free monthly newsletter providing summaries, analyses, insights, and commentaries on security: computer and otherwise.

For back issues, or to subscribe, visit Crypto-Gram’s web page.

These same essays and news items appear in the Schneier on Security blog, along with a lively and intelligent comment section. An RSS feed is available.

In this issue:

- Critical Windows Vulnerability Discovered by NSA

- Securing Tiffany’s Move

- Clearview AI and Facial Recognition

- SIM Hijacking

- Brazil Charges Glenn Greenwald with Cybercrimes

- Half a Million IoT Device Passwords Published

- Apple Abandoned Plans for Encrypted iCloud Backup after FBI Complained

- Technical Report of the Bezos Phone Hack

- Smartphone Election in Washington State

- Modern Mass Surveillance: Identify, Correlate, Discriminate

- Google Receives Geofence Warrants

- Customer Tracking at Ralphs Grocery Store

- Collating Hacked Data Sets

- US Department of Interior Grounding All Drones

- NSA Security Awareness Posters

- Attacking Driverless Cars with Projected Images

- New Research on the Adtech Industry

- Tree Code

- A New Clue for the Kryptos Sculpture

- New Ransomware Targets Industrial Control Systems

- Security in 2020: Revisited

- Apple’s Tracking-Prevention Feature in Safari has a Privacy Bug

- Crypto AG Was Owned by the CIA

- Companies that Scrape Your Email

- A US Data Protection Agency

- DNSSEC Keysigning Ceremony Postponed Because of Locked Safe

- Upcoming Speaking Engagements

Critical Windows Vulnerability Discovered by NSA

[2020.01.15] Yesterday’s Microsoft Windows patches included a fix for a critical vulnerability in the system’s crypto library.

A spoofing vulnerability exists in the way Windows CryptoAPI (Crypt32.dll) validates Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) certificates.

An attacker could exploit the vulnerability by using a spoofed code-signing certificate to sign a malicious executable, making it appear the file was from a trusted, legitimate source. The user would have no way of knowing the file was malicious, because the digital signature would appear to be from a trusted provider.

A successful exploit could also allow the attacker to conduct man-in-the-middle attacks and decrypt confidential information on user connections to the affected software.

That’s really bad, and you should all patch your system right now, before you finish reading this blog post.

This is a zero-day vulnerability, meaning that it was not detected in the wild before the patch was released. It was discovered by security researchers. Interestingly, it was discovered by NSA security researchers, and the NSA security advisory gives a lot more information about it than the Microsoft advisory does.

Exploitation of the vulnerability allows attackers to defeat trusted network connections and deliver executable code while appearing as legitimately trusted entities. Examples where validation of trust may be impacted include:

- HTTPS connections

- Signed files and emails

- Signed executable code launched as user-mode processes

The vulnerability places Windows endpoints at risk to a broad range of exploitation vectors. NSA assesses the vulnerability to be severe and that sophisticated cyber actors will understand the underlying flaw very quickly and, if exploited, would render the previously mentioned platforms as fundamentally vulnerable.The consequences of not patching the vulnerability are severe and widespread. Remote exploitation tools will likely be made quickly and widely available.Rapid adoption of the patch is the only known mitigation at this time and should be the primary focus for all network owners.

Early yesterday morning, NSA’s Cybersecurity Directorate head Anne Neuberger hosted a media call where she talked about the vulnerability and—to my shock—took questions from the attendees. According to her, the NSA discovered this vulnerability as part of its security research. (If it found it in some other nation’s cyberweapons stash—my personal favorite theory—she declined to say.) She did not answer when asked how long ago the NSA discovered the vulnerability. She said that this is not the first time the NSA sent Microsoft a vulnerability to fix, but it was the first time it has publicly taken credit for the discovery. The reason is that the NSA is trying to rebuild trust with the security community, and this disclosure is a result of its new initiative to share findings more quickly and more often.

Barring any other information, I would take the NSA at its word here. So, good for it.

And—seriously—patch your systems now: Windows 10 and Windows Server 2016/2019. Assume that this vulnerability has already been weaponized, probably by criminals and certainly by major governments. Even assume that the NSA is using this vulnerability—why wouldn’t it?

Ars Technica article. Wired article. CERT advisory.

EDITED TO ADD: Washington Post article.

EDITED TO ADD (1/16): The attack was demonstrated in less than 24 hours.

Brian Krebs blog post.

Securing Tiffany’s Move

[2020.01.16] Story of how Tiffany & Company moved all of its inventory from one store to another. Short summary: careful auditing and a lot of police.

Clearview AI and Facial Recognition

[2020.01.20] The New York Times has a long story about Clearview AI, a small company that scrapes identified photos of people from pretty much everywhere, and then uses unstated magical AI technology to identify people in other photos.

His tiny company, Clearview AI, devised a groundbreaking facial recognition app. You take a picture of a person, upload it and get to see public photos of that person, along with links to where those photos appeared. The system—whose backbone is a database of more than three billion images that Clearview claims to have scraped from Facebook, YouTube, Venmo and millions of other websites—goes far beyond anything ever constructed by the United States government or Silicon Valley giants.

Federal and state law enforcement officers said that while they had only limited knowledge of how Clearview works and who is behind it, they had used its app to help solve shoplifting, identity theft, credit card fraud, murder and child sexual exploitation cases.

[…]

But without public scrutiny, more than 600 law enforcement agencies have started using Clearview in the past year, according to the company, which declined to provide a list. The computer code underlying its app, analyzed by The New York Times, includes programming language to pair it with augmented-reality glasses; users would potentially be able to identify every person they saw. The tool could identify activists at a protest or an attractive stranger on the subway, revealing not just their names but where they lived, what they did and whom they knew.

And it’s not just law enforcement: Clearview has also licensed the app to at least a handful of companies for security purposes.

Another article.

EDITED TO ADD (1/23): Twitter told the company to stop scraping its photos.

SIM Hijacking

[2020.01.21] SIM hijacking—or SIM swapping—is an attack where a fraudster contacts your cell phone provider and convinces them to switch your account to a phone that they control. Since your smartphone often serves as a security measure or backup verification system, this allows the fraudster to take over other accounts of yours. Sometimes this involves people inside the phone companies.

Phone companies have added security measures since this attack became popular and public, but a new study (news article) shows that the measures aren’t helping:

We examined the authentication procedures used by five pre-paid wireless carriers when a customer attempted to change their SIM card. These procedures are an important line of defense against attackers who seek to hijack victims’ phone numbers by posing as the victim and calling the carrier to request that service be transferred to a SIM card the attacker possesses. We found that all five carriers used insecure authentication challenges that could be easily subverted by attackers.We also found that attackers generally only needed to target the most vulnerable authentication challenges, because the rest could be bypassed.

It’s a classic security vs. usability trade-off. The phone companies want to provide easy customer service for their legitimate customers, and that system is what’s being exploited by the SIM hijackers. Companies could make the fraud harder, but it would necessarily also make it harder for legitimate customers to modify their accounts.

Brazil Charges Glenn Greenwald with Cybercrimes

[2020.01.21] Glenn Greenwald has been charged with cybercrimes in Brazil, stemming from publishing information and documents that were embarrassing to the government. The charges are that he actively helped the people who actually did the hacking:

Citing intercepted messages between Mr. Greenwald and the hackers, prosecutors say the journalist played a “clear role in facilitating the commission of a crime.”

For instance, prosecutors contend that Mr. Greenwald encouraged the hackers to delete archives that had already been shared with The Intercept Brasil, in order to cover their tracks.

Prosecutors also say that Mr. Greenwald was communicating with the hackers while they were actively monitoring private chats on Telegram, a messaging app. The complaint charged six other individuals, including four who were detained last year in connection with the cellphone hacking.

This isn’t new, or unique to Brazil. Last year, Julian Assange was charged by the US with doing essentially the same thing with Chelsea Manning:

The indictment alleges that in March 2010, Assange engaged in a conspiracy with Chelsea Manning, a former intelligence analyst in the U.S. Army, to assist Manning in cracking a password stored on U.S. Department of Defense computers connected to the Secret Internet Protocol Network (SIPRNet), a U.S. government network used for classified documents and communications. Manning, who had access to the computers in connection with her duties as an intelligence analyst, was using the computers to download classified records to transmit to WikiLeaks. Cracking the password would have allowed Manning to log on to the computers under a username that did not belong to her. Such a deceptive measure would have made it more difficult for investigators to determine the source of the illegal disclosures.

During the conspiracy, Manning and Assange engaged in real-time discussions regarding Manning’s transmission of classified records to Assange. The discussions also reflect Assange actively encouraging Manning to provide more information. During an exchange, Manning told Assange that “after this upload, that’s all I really have got left.” To which Assange replied, “curious eyes never run dry in my experience.”

Good commentary on the Assange case here.

It’s too early for any commentary on the Greenwald case. Lots of news articles are essentially saying the same thing. I’ll post more news when there is some.

EDITED TO ADD (2/12): Marcy Wheeler compares the Greenwald case with the Assange case.

Half a Million IoT Device Passwords Published

[2020.01.22] It’s a list of easy-to-guess passwords for IoT devices on the Internet as recently as last October and November. Useful for anyone putting together a bot network:

A hacker has published this week a massive list of Telnet credentials for more than 515,000 servers, home routers, and IoT (Internet of Things) “smart” devices.

The list, which was published on a popular hacking forum, includes each device’s IP address, along with a username and password for the Telnet service, a remote access protocol that can be used to control devices over the internet.

According to experts to who ZDNet spoke this week, and a statement from the leaker himself, the list was compiled by scanning the entire internet for devices that were exposing their Telnet port. The hacker than tried using (1) factory-set default usernames and passwords, or (2) custom, but easy-to-guess password combinations.

Apple Abandoned Plans for Encrypted iCloud Backup after FBI Complained

[2020.01.23] This is new from Reuters:

More than two years ago, Apple told the FBI that it planned to offer users end-to-end encryption when storing their phone data on iCloud, according to one current and three former FBI officials and one current and one former Apple employee.

Under that plan, primarily designed to thwart hackers, Apple would no longer have a key to unlock the encrypted data, meaning it would not be able to turn material over to authorities in a readable form even under court order.

In private talks with Apple soon after, representatives of the FBI’s cyber crime agents and its operational technology division objected to the plan, arguing it would deny them the most effective means for gaining evidence against iPhone-using suspects, the government sources said.

When Apple spoke privately to the FBI about its work on phone security the following year, the end-to-end encryption plan had been dropped, according to the six sources. Reuters could not determine why exactly Apple dropped the plan.

EDITED TO ADD (2/13): Android has enrypted backups.

Technical Report of the Bezos Phone Hack

[2020.01.24] Motherboard obtained and published the technical report on the hack of Jeff Bezos’s phone, which is being attributed to Saudi Arabia, specifically to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

…investigators set up a secure lab to examine the phone and its artifacts and spent two days poring over the device but were unable to find any malware on it. Instead, they only found a suspicious video file sent to Bezos on May 1, 2018 that “appears to be an Arabic language promotional film about telecommunications.”

That file shows an image of the Saudi Arabian flag and Swedish flags and arrived with an encrypted downloader. Because the downloader was encrypted this delayed or further prevented “study of the code delivered along with the video.”

Investigators determined the video or downloader were suspicious only because Bezos’ phone subsequently began transmitting large amounts of data. “[W]ithin hours of the encrypted downloader being received, a massive and unauthorized exfiltration of data from Bezos’ phone began, continuing and escalating for months thereafter,” the report states.

“The amount of data being transmitted out of Bezos’ phone changed dramatically after receiving the WhatsApp video file and never returned to baseline. Following execution of the encrypted downloader sent from MBS’ account, egress on the device immediately jumped by approximately 29,000 percent,” it notes. “Forensic artifacts show that in the six (6) months prior to receiving the WhatsApp video, Bezos’ phone had an average of 430KB of egress per day, fairly typical of an iPhone. Within hours of the WhatsApp video, egress jumped to 126MB. The phone maintained an unusually high average of 101MB of egress data per day for months thereafter, including many massive and highly atypical spikes of egress data.”

The Motherboard article also quotes forensic experts on the report:

A mobile forensic expert told Motherboard that the investigation as depicted in the report is significantly incomplete and would only have provided the investigators with about 50 percent of what they needed, especially if this is a nation-state attack. She says the iTunes backup and other extractions they did would get them only messages, photo files, contacts and other files that the user is interested in saving from their applications, but not the core files.

“They would need to use a tool like Graykey or Cellebrite Premium or do a jailbreak to get a look at the full file system. That’s where that state-sponsored malware is going to be found. Good state-sponsored malware should never show up in a backup,” said Sarah Edwards, an author and teacher of mobile forensics for the SANS Institute.

“The full file system is getting into the device and getting every single file on there—the whole operating system, the application data, the databases that will not be backed up. So really the in-depth analysis should be done on that full file system, for this level of investigation anyway. I would have insisted on that right from the start.”

The investigators do note on the last page of their report that they need to jailbreak Bezos’s phone to examine the root file system. Edwards said this would indeed get them everything they would need to search for persistent spyware like the kind created and sold by the NSO Group. But the report doesn’t indicate if that did get done.

Smartphone Election in Washington State

[2020.01.27] This year:

King County voters will be able to use their name and birthdate to log in to a Web portal through the Internet browser on their phones, says Bryan Finney, the CEO of Democracy Live, the Seattle-based voting company providing the technology.

Once voters have completed their ballots, they must verify their submissions and then submit a signature on the touch screen of their device.

Finney says election officials in Washington are adept at signature verification because the state votes entirely by mail. That will be the way people are caught if they log in to the system under false pretenses and try to vote as someone else.

The King County elections office plans to print out the ballots submitted electronically by voters whose signatures match and count the papers alongside the votes submitted through traditional routes.

While advocates say this creates an auditable paper trail, many security experts say that because the ballots cross the Internet before they are printed, any subsequent audits on them would be moot. If a cyberattack occurred, an audit could essentially require double-checking ballots that may already have been altered, says Buell.

Of course it’s not an auditable paper trail. There’s a reason why security experts use the phrase “voter-verifiable paper ballots.” A centralized printout of a received Internet message is not voter verifiable.

Another news article.

Modern Mass Surveillance: Identify, Correlate, Discriminate

[2020.01.27] Communities across the United States are starting to ban facial recognition technologies. In May of last year, San Francisco banned facial recognition; the neighboring city of Oakland soon followed, as did Somerville and Brookline in Massachusetts (a statewide ban may follow). In December, San Diego suspended a facial recognition program in advance of a new statewide law, which declared it illegal, coming into effect. Forty major music festivals pledged not to use the technology, and activists are calling for a nationwide ban. Many Democratic presidential candidates support at least a partial ban on the technology.

These efforts are well-intentioned, but facial recognition bans are the wrong way to fight against modern surveillance. Focusing on one particular identification method misconstrues the nature of the surveillance society we’re in the process of building. Ubiquitous mass surveillance is increasingly the norm. In countries like China, a surveillance infrastructure is being built by the government for social control. In countries like the United States, it’s being built by corporations in order to influence our buying behavior, and is incidentally used by the government.

In all cases, modern mass surveillance has three broad components: identification, correlation and discrimination. Let’s take them in turn.

Facial recognition is a technology that can be used to identify people without their knowledge or consent. It relies on the prevalence of cameras, which are becoming both more powerful and smaller, and machine learning technologies that can match the output of these cameras with images from a database of existing photos.

But that’s just one identification technology among many. People can be identified at a distance by their heartbeat or by their gait, using a laser-based system. Cameras are so good that they can read fingerprints and iris patterns from meters away. And even without any of these technologies, we can always be identified because our smartphones broadcast unique numbers called MAC addresses. Other things identify us as well: our phone numbers, our credit card numbers, the license plates on our cars. China, for example, uses multiple identification technologies to support its surveillance state.

Once we are identified, the data about who we are and what we are doing can be correlated with other data collected at other times. This might be movement data, which can be used to “follow” us as we move throughout our day. It can be purchasing data, Internet browsing data, or data about who we talk to via email or text. It might be data about our income, ethnicity, lifestyle, profession and interests. There is an entire industry of data brokers who make a living analyzing and augmenting data about who we are—using surveillance data collected by all sorts of companies and then sold without our knowledge or consent.

There is a huge—and almost entirely unregulated—data broker industry in the United States that trades on our information. This is how large Internet companies like Google and Facebook make their money. It’s not just that they know who we are, it’s that they correlate what they know about us to create profiles about who we are and what our interests are. This is why many companies buy license plate data from states. It’s also why companies like Google are buying health records, and part of the reason Google bought the company Fitbit, along with all of its data.

The whole purpose of this process is for companies—and governments—to treat individuals differently. We are shown different ads on the Internet and receive different offers for credit cards. Smart billboards display different advertisements based on who we are. In the future, we might be treated differently when we walk into a store, just as we currently are when we visit websites.

The point is that it doesn’t matter which technology is used to identify people. That there currently is no comprehensive database of heartbeats or gaits doesn’t make the technologies that gather them any less effective. And most of the time, it doesn’t matter if identification isn’t tied to a real name. What’s important is that we can be consistently identified over time. We might be completely anonymous in a system that uses unique cookies to track us as we browse the Internet, but the same process of correlation and discrimination still occurs. It’s the same with faces; we can be tracked as we move around a store or shopping mall, even if that tracking isn’t tied to a specific name. And that anonymity is fragile: If we ever order something online with a credit card, or purchase something with a credit card in a store, then suddenly our real names are attached to what was anonymous tracking information.

Regulating this system means addressing all three steps of the process. A ban on facial recognition won’t make any difference if, in response, surveillance systems switch to identifying people by smartphone MAC addresses. The problem is that we are being identified without our knowledge or consent, and society needs rules about when that is permissible.

Similarly, we need rules about how our data can be combined with other data, and then bought and sold without our knowledge or consent. The data broker industry is almost entirely unregulated; there’s only one law—passed in Vermont in 2018—that requires data brokers to register and explain in broad terms what kind of data they collect. The large Internet surveillance companies like Facebook and Google collect dossiers on us are more detailed than those of any police state of the previous century. Reasonable laws would prevent the worst of their abuses.

Finally, we need better rules about when and how it is permissible for companies to discriminate. Discrimination based on protected characteristics like race and gender is already illegal, but those rules are ineffectual against the current technologies of surveillance and control. When people can be identified and their data correlated at a speed and scale previously unseen, we need new rules.

Today, facial recognition technologies are receiving the brunt of the tech backlash, but focusing on them misses the point. We need to have a serious conversation about all the technologies of identification, correlation and discrimination, and decide how much we as a society want to be spied on by governments and corporations—and what sorts of influence we want them to have over our lives.

This essay previously appeared in the New York Times.

EDITED TO ADD: Rereading this post-publication, I see that it comes off as overly critical of those who are doing activism in this space. Writing the piece, I wasn’t thinking about political tactics. I was thinking about the technologies that support surveillance capitalism, and law enforcement’s usage of that corporate platform. Of course it makes sense to focus on face recognition in the short term. It’s something that’s easy to explain, viscerally creepy, and obviously actionable. It also makes sense to focus specifically on law enforcement’s use of the technology; there are clear civil and constitutional rights issues. The fact that law enforcement is so deeply involved in the technology’s marketing feels wrong. And the technology is currently being deployed in Hong Kong against political protesters. It’s why the issue has momentum, and why we’ve gotten the small wins we’ve had. (The EU is considering a five-year ban on face recognition technologies.) Those wins build momentum, which lead to more wins. I should have been kinder to those in the trenches.

If you want to help, sign the petition from Public Voice calling on a moratorium on facial recognition technology for mass surveillance. Or write to your US congressperson and demand similar action. There’s more information from EFF and EPIC.

Google Receives Geofence Warrants

[2020.01.28] Sometimes it’s hard to tell the corporate surveillance operations from the government ones:

Google reportedly has a database called Sensorvault in which it stores location data for millions of devices going back almost a decade.

The article is about geofence warrants, where the police go to companies like Google and ask for information about every device in a particular geographic area at a particular time. In 2013, we learned from Edward Snowden that the NSA does this worldwide. Its program is called CO-TRAVELLER. The NSA claims it stopped doing that in 2014—probably just stopped doing it in the US—but why should it bother when the government can just get the data from Google.

Both the New York Times and EFF have written about Sensorvault.

Customer Tracking at Ralphs Grocery Store

[2020.01.29] To comply with California’s new data privacy law, companies that collect information on consumers and users are forced to be more transparent about it. Sometimes the results are creepy. Here’s an article about Ralphs, a California supermarket chain owned by Kroger:

…the form proceeds to state that, as part of signing up for a rewards card, Ralphs “may collect” information such as “your level of education, type of employment, information about your health and information about insurance coverage you might carry.”

It says Ralphs may pry into “financial and payment information like your bank account, credit and debit card numbers, and your credit history.”

Wait, it gets even better.

Ralphs says it’s gathering “behavioral information” such as “your purchase and transaction histories” and “geolocation data,” which could mean the specific Ralphs aisles you browse or could mean the places you go when not shopping for groceries, thanks to the tracking capability of your smartphone.

Ralphs also reserves the right to go after “information about what you do online” and says it will make “inferences” about your interests “based on analysis of other information we have collected.”

Other information? This can include files from “consumer research firms”—read: professional data brokers—and “public databases,” such as property records and bankruptcy filings.

The reaction from John Votava, a Ralphs spokesman:

“I can understand why it raises eyebrows,” he said. We may need to change the wording on the form.”

That’s the company’s solution. Don’t spy on people less, just change the wording so they don’t realize it.

More consumer protection laws will be required.

Collating Hacked Data Sets

[2020.01.30] Two Harvard undergraduates completed a project where they went out on the dark web and found a bunch of stolen datasets. Then they correlated all the information, and combined it with additional, publicly available, information. No surprise: the result was much more detailed and personal.

“What we were able to do is alarming because we can now find vulnerabilities in people’s online presence very quickly,” Metropolitansky said. “For instance, if I can aggregate all the leaked credentials associated with you in one place, then I can see the passwords and usernames that you use over and over again.”

Of the 96,000 passwords contained in the dataset the students used, only 26,000 were unique.

“We also showed that a cyber criminal doesn’t have to have a specific victim in mind. They can now search for victims who meet a certain set of criteria,” Metropolitansky said.

For example, in less than 10 seconds she produced a dataset with more than 1,000 people who have high net worth, are married, have children, and also have a username or password on a cheating website. Another query pulled up a list of senior-level politicians, revealing the credit scores, phone numbers, and addresses of three U.S. senators, three U.S. representatives, the mayor of Washington, D.C., and a Cabinet member.

“Hopefully, this serves as a wake-up call that leaks are much more dangerous than we think they are,” Metropolitansky said. “We’re two college students. If someone really wanted to do some damage, I’m sure they could use these same techniques to do something horrible.”

That’s about right.

And you can be sure that the world’s major intelligence organizations have already done all of this.

US Department of Interior Grounding All Drones

[2020.01.31] The Department of Interior is grounding all non-emergency drones due to security concerns:

The order comes amid a spate of warnings and bans at multiple government agencies, including the Department of Defense, about possible vulnerabilities in Chinese-made drone systems that could be allowing Beijing to conduct espionage. The Army banned the use of Chinese-made DJI drones three years ago following warnings from the Navy about “highly vulnerable” drone systems.

One memo drafted by the Navy & Marine Corps Small Tactical Unmanned Aircraft Systems Program Manager has warned “images, video and flight records could be uploaded to unsecured servers in other countries via live streaming.” The Navy has also warned adversaries may view video and metadata from drone systems even though the air vehicle is encrypted. The Department of Homeland Security previously warned the private sector their data may be pilfered off if they use commercial drone systems made in China.

I’m actually not that worried about this risk. Data moving across the Internet is obvious—it’s too easy for a country that tries this to get caught. I am much more worried about remote kill switches in the equipment.

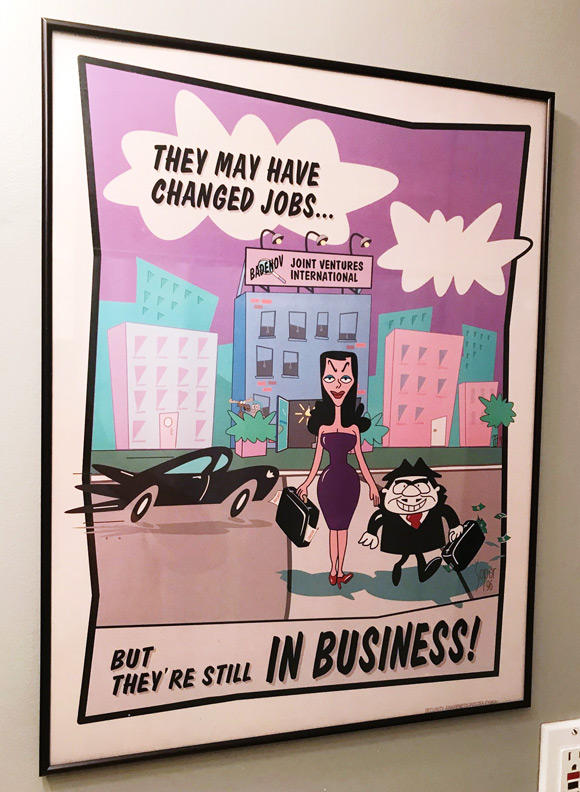

NSA Security Awareness Posters

[2020.01.31] From a FOIA request, over a hundred old NSA security awareness posters. Here are the BBC’s favorites. Here are Motherboard’s favorites.

I have a related personal story. Back in 1993, during the first Crypto Wars, I and a handful of other academic cryptographers visited the NSA for some meeting or another. These sorts of security awareness posters were everywhere, but there was one I especially liked—and I asked for a copy. I have no idea who, but someone at the NSA mailed it to me. It’s currently framed and on my wall.

I’ll bet that the NSA didn’t get permission from Jay Ward Productions.

Attacking Driverless Cars with Projected Images

[2020.02.03] Interesting research—”Phantom Attacks Against Advanced Driving Assistance Systems“:

Abstract: The absence of deployed vehicular communication systems, which prevents the advanced driving assistance systems (ADASs) and autopilots of semi/fully autonomous cars to validate their virtual perception regarding the physical environment surrounding the car with a third party, has been exploited in various attacks suggested by researchers. Since the application of these attacks comes with a cost (exposure of the attacker’s identity), the delicate exposure vs. application balance has held, and attacks of this kind have not yet been encountered in the wild. In this paper, we investigate a new perceptual challenge that causes the ADASs and autopilots of semi/fully autonomous to consider depthless objects (phantoms) as real. We show how attackers can exploit this perceptual challenge to apply phantom attacks and change the abovementioned balance, without the need to physically approach the attack scene, by projecting a phantom via a drone equipped with a portable projector or by presenting a phantom on a hacked digital billboard that faces the Internet and is located near roads. We show that the car industry has not considered this type of attack by demonstrating the attack on today’s most advanced ADAS and autopilot technologies: Mobileye 630 PRO and the Tesla Model X, HW 2.5; our experiments show that when presented with various phantoms, a car’s ADAS or autopilot considers the phantoms as real objects, causing these systems to trigger the brakes, steer into the lane of oncoming traffic, and issue notifications about fake road signs. In order to mitigate this attack, we present a model that analyzes a detected object’s context, surface, and reflected light, which is capable of detecting phantoms with 0.99 AUC. Finally, we explain why the deployment of vehicular communication systems might reduce attackers’ opportunities to apply phantom attacks but won’t eliminate them.

The paper will be presented at CyberTech at the end of the month.

New Research on the Adtech Industry

[2020.02.04] The Norwegian Consumer Council has published an extensive report about how the adtech industry violates consumer privacy. At the same time, it is filing three legal complaints against six companies in this space. From a Twitter summary:

1. [thread] We are filing legal complaints against six companies based on our research, revealing systematic breaches to privacy, by shadowy #OutOfControl #adtech companies gathering & sharing heaps of personal data. https://forbrukerradet.no/out-of-control/#GDPR… #privacy

2. We observed how ten apps transmitted user data to at least 135 different third parties involved in advertising and/or behavioural profiling, exposing (yet again) a vast network of companies monetizing user data and using it for their own purposes.

3. Dating app @Grindr shared detailed user data with a large number of third parties. Data included the fact that you are using the app (clear indication of sexual orientation), IP address (personal data), Advertising ID, GPS location (very revealing), age, and gender.

From a news article:

The researchers also reported that the OkCupid app sent a user’s ethnicity and answers to personal profile questions—like “Have you used psychedelic drugs?”—to a firm that helps companies tailor marketing messages to users. The Times found that the OkCupid site had recently posted a list of more than 300 advertising and analytics “partners” with which it may share users’ information.

This is really good research exposing the inner workings of a very secretive industry.

Tree Code

[2020.02.05] Artist Katie Holten has developed a tree code (basically, a font in trees), and New York City is using it to plant secret messages in parks.

A New Clue for the Kryptos Sculpture

[2020.02.06] Jim Sanborn, who designed the Kryptos sculpture in a CIA courtyard, has released another clue to the still-unsolved part 4. I think he’s getting tired of waiting.

Did we mention Mr. Sanborn is 74?

Holding on to one of the world’s most enticing secrets can be stressful. Some would-be codebreakers have appeared at his home.

Many felt they had solved the puzzle, and wanted to check with Mr. Sanborn. Sometimes forcefully. Sometimes, in person.

Elonka Dunin, a game developer and consultant who has created a rich page of background information on the sculpture and oversees the best known online community of thousands of Kryptos fans, said that some who contact her (sometimes also at home) are obsessive and appear to have tipped into mental illness. “I am always gentle to them and do my best to listen to them,” she said.

Mr. Sanborn has set up systems to allow people to check their proposed solutions without having to contact him directly. The most recent incarnation is an email-based process with a fee of $50 to submit a potential solution. He receives regular inquiries, so far none of them successful.

The ongoing process is exhausting, he said, adding “It’s not something I thought I would be doing 30 years on.”

Another news article.

EDITED TO ADD (2/13): Another article.

New Ransomware Targets Industrial Control Systems

[2020.02.07] EKANS is a new ransomware that targets industrial control systems:

But EKANS also uses another trick to ratchet up the pain: It’s designed to terminate 64 different software processes on victim computers, including many that are specific to industrial control systems. That allows it to then encrypt the data that those control system programs interact with. While crude compared to other malware purpose-built for industrial sabotage, that targeting can nonetheless break the software used to monitor infrastructure, like an oil firm’s pipelines or a factory’s robots. That could have potentially dangerous consequences, like preventing staff from remotely monitoring or controlling the equipment’s operation.

EKANS is actually the second ransomware to hit industrial control systems. According to Dragos, another ransomware strain known as Megacortex that first appeared last spring included all of the same industrial control system process-killing features, and may in fact be a predecessor to EKANS developed by the same hackers. But because Megacortex also terminated hundreds of other processes, its industrial-control-system targeted features went largely overlooked.

Speculation is that this is criminal in origin, and not the work of a government.

It’s also the first malware that is named after a Pokemon character.

Security in 2020: Revisited

[2020.02.07] Ten years ago, I wrote an essay: “Security in 2020.” Well, it’s finally 2020. I think I did pretty well. Here’s what I said back then:

There’s really no such thing as security in the abstract. Security can only be defined in relation to something else. You’re secure from something or against something. In the next 10 years, the traditional definition of IT security—that it protects you from hackers, criminals, and other bad guys—will undergo a radical shift. Instead of protecting you from the bad guys, it will increasingly protect businesses and their business models from you.

Ten years ago, the big conceptual change in IT security was deperimeterization. A wordlike grouping of 18 letters with both a prefix and a suffix, it has to be the ugliest word our industry invented. The concept, though—the dissolution of the strict boundaries between the internal and external network—was both real and important.

There’s more deperimeterization today than there ever was. Customer and partner access, guest access, outsourced e-mail, VPNs; to the extent there is an organizational network boundary, it’s so full of holes that it’s sometimes easier to pretend it isn’t there. The most important change, though, is conceptual. We used to think of a network as a fortress, with the good guys on the inside and the bad guys on the outside, and walls and gates and guards to ensure that only the good guys got inside. Modern networks are more like cities, dynamic and complex entities with many different boundaries within them. The access, authorization, and trust relationships are even more complicated.

Today, two other conceptual changes matter. The first is consumerization. Another ponderous invented word, it’s the idea that consumers get the cool new gadgets first, and demand to do their work on them. Employees already have their laptops configured just the way they like them, and they don’t want another one just for getting through the corporate VPN. They’re already reading their mail on their BlackBerrys or iPads. They already have a home computer, and it’s cooler than the standard issue IT department machine. Network administrators are increasingly losing control over clients.

This trend will only increase. Consumer devices will become trendier, cheaper, and more integrated; and younger people are already used to using their own stuff on their school networks. It’s a recapitulation of the PC revolution. The centralized computer center concept was shaken by people buying PCs to run VisiCalc; now it’s iPads and Android smartphones.

The second conceptual change comes from cloud computing: our increasing tendency to store our data elsewhere. Call it decentralization: our email, photos, books, music, and documents are stored somewhere, and accessible to us through our consumer devices. The younger you are, the more you expect to get your digital stuff on the closest screen available. This is an important trend, because it signals the end of the hardware and operating system battles we’ve all lived with. Windows vs. Mac doesn’t matter when all you need is a web browser. Computers become temporary; user backup becomes irrelevant. It’s all out there somewhere—and users are increasingly losing control over their data.

During the next 10 years, three new conceptual changes will emerge, two of which we can already see the beginnings of. The first I’ll call deconcentration. The general-purpose computer is dying and being replaced by special-purpose devices. Some of them, like the iPhone, seem general purpose but are strictly controlled by their providers. Others, like Internet-enabled game machines or digital cameras, are truly special purpose. In 10 years, most computers will be small, specialized, and ubiquitous.

Even on what are ostensibly general-purpose devices, we’re seeing more special-purpose applications. Sure, you could use the iPhone’s web browser to access the New York Times website, but it’s much easier to use the NYT’s special iPhone app. As computers become smaller and cheaper, this trend will only continue. It’ll be easier to use special-purpose hardware and software. And companies, wanting more control over their users’ experience, will push this trend.

The second is decustomerization—now I get to invent the really ugly words—the idea that we get more of our IT functionality without any business relationship. We’re all part of this trend: every search engine gives away its services in exchange for the ability to advertise. It’s not just Google and Bing; most webmail and social networking sites offer free basic service in exchange for advertising, possibly with premium services for money. Most websites, even useful ones that take the place of client software, are free; they are either run altruistically or to facilitate advertising.

Soon it will be hardware. In 1999, Internet startup FreePC tried to make money by giving away computers in exchange for the ability to monitor users’ surfing and purchasing habits. The company failed, but computers have only gotten cheaper since then. It won’t be long before giving away netbooks in exchange for advertising will be a viable business. Or giving away digital cameras. Already there are companies that give away long-distance minutes in exchange for advertising. Free cell phones aren’t far off. Of course, not all IT hardware will be free. Some of the new cool hardware will cost too much to be free, and there will always be a need for concentrated computing power close to the user—game systems are an obvious example—but those will be the exception. Where the hardware costs too much to just give away, however, we’ll see free or highly subsidized hardware in exchange for locked-in service; that’s already the way cell phones are sold.

This is important because it destroys what’s left of the normal business relationship between IT companies and their users. We’re not Google’s customers; we’re Google’s product that they sell to their customers. It’s a three-way relationship: us, the IT service provider, and the advertiser or data buyer. And as these noncustomer IT relationships proliferate, we’ll see more IT companies treating us as products. If I buy a Dell computer, then I’m obviously a Dell customer; but if I get a Dell computer for free in exchange for access to my life, it’s much less obvious whom I’m entering a business relationship with. Facebook’s continual ratcheting down of user privacy in order to satisfy its actual customers—the advertisers—and enhance its revenue is just a hint of what’s to come.

The third conceptual change I’ve termed depersonization: computing that removes the user, either partially or entirely. Expect to see more software agents: programs that do things on your behalf, such as prioritize your email based on your observed preferences or send you personalized sales announcements based on your past behavior. The “people who liked this also liked” feature on many retail websites is just the beginning. A website that alerts you if a plane ticket to your favorite destination drops below a certain price is simplistic but useful, and some sites already offer this functionality. Ten years won’t be enough time to solve the serious artificial intelligence problems required to fully realize intelligent agents, but the agents of that time will be both sophisticated and commonplace, and they’ll need less direct input from you.

Similarly, connecting objects to the Internet will soon be cheap enough to be viable. There’s already considerable research into Internet-enabled medical devices, smart power grids that communicate with smart phones, and networked automobiles. Nike sneakers can already communicate with your iPhone. Your phone already tells the network where you are. Internet-enabled appliances are already in limited use, but soon they will be the norm. Businesses will acquire smart HVAC units, smart elevators, and smart inventory systems. And, as short-range communications—like RFID and Bluetooth—become cheaper, everything becomes smart.

The “Internet of things” won’t need you to communicate. The smart appliances in your smart home will talk directly to the power company. Your smart car will talk to road sensors and, eventually, other cars. Your clothes will talk to your dry cleaner. Your phone will talk to vending machines; they already do in some countries. The ramifications of this are hard to imagine; it’s likely to be weirder and less orderly than the contemporary press describes it. But certainly smart objects will be talking about you, and you probably won’t have much control over what they’re saying.

One old trend: deperimeterization. Two current trends: consumerization and decentralization. Three future trends: deconcentration, decustomerization, and depersonization. That’s IT in 2020—it’s not under your control, it’s doing things without your knowledge and consent, and it’s not necessarily acting in your best interests. And this is how things will be when they’re working as they’re intended to work; I haven’t even started talking about the bad guys yet.

That’s because IT security in 2020 will be less about protecting you from traditional bad guys, and more about protecting corporate business models from you. Deperimeterization assumes everyone is untrusted until proven otherwise. Consumerization requires networks to assume all user devices are untrustworthy until proven otherwise. Decentralization and deconcentration won’t work if you’re able to hack the devices to run unauthorized software or access unauthorized data. Deconsumerization won’t be viable unless you’re unable to bypass the ads, or whatever the vendor uses to monetize you. And depersonization requires the autonomous devices to be, well, autonomous.

In 2020—10 years from now—Moore’s Law predicts that computers will be 100 times more powerful. That’ll change things in ways we can’t know, but we do know that human nature never changes. Cory Doctorow rightly pointed out that all complex ecosystems have parasites. Society’s traditional parasites are criminals, but a broader definition makes more sense here. As we users lose control of those systems and IT providers gain control for their own purposes, the definition of “parasite” will shift. Whether they’re criminals trying to drain your bank account, movie watchers trying to bypass whatever copy protection studios are using to protect their profits, or Facebook users trying to use the service without giving up their privacy or being forced to watch ads, parasites will continue to try to take advantage of IT systems. They’ll exist, just as they always have existed, and—like today—security is going to have a hard time keeping up with them.

Welcome to the future. Companies will use technical security measures, backed up by legal security measures, to protect their business models. And unless you’re a model user, the parasite will be you.

My only real complaint with the essay is that I used “decentralization” in a nonstandard manner, and didn’t explain it well. I meant that our personal data will become decentralized; instead of it all being on our own computers, it will be on the computers of various cloud providers. But that causes a massive centralization of all of our data. I should have explicitly called out the risks of that.

Otherwise, I’m happy with what I wrote ten years ago.

Apple’s Tracking-Prevention Feature in Safari has a Privacy Bug

[2020.02.10] Last month, engineers at Google published a very curious privacy bug in Apple’s Safari web browser. Apple’s Intelligent Tracking Prevention, a feature designed to reduce user tracking, has vulnerabilities that themselves allow user tracking. Some details:

ITP detects and blocks tracking on the web. When you visit a few websites that happen to load the same third-party resource, ITP detects the domain hosting the resource as a potential tracker and from then on sanitizes web requests to that domain to limit tracking. Tracker domains are added to Safari’s internal, on-device ITP list. When future third-party requests are made to a domain on the ITP list, Safari will modify them to remove some information it believes may allow tracking the user (such as cookies).

[…]

The details should come as a surprise to everyone because it turns out that ITP could effectively be used for:

- information leaks: detecting websites visited by the user (web browsing history hijacking, stealing a list of visited sites)

- tracking the user with ITP, making the mechanism function like a cookie

- fingerprinting the user: in ways similar to the HSTS fingerprint, but perhaps a bit better

I am sure we all agree that we would not expect a privacy feature meant to protect from tracking to effectively enable tracking, and also accidentally allowing any website out there to steal its visitors’ web browsing history. But web architecture is complex, and the consequence is that this is exactly the case.

Apple fixed this vulnerability in December, a month before Google published.

If there’s any lesson here, it’s that privacy is hard—and that privacy engineering is even harder. It’s not that we shouldn’t try, but we should recognize that it’s easy to get it wrong.

Crypto AG Was Owned by the CIA

[2020.02.11] The Swiss cryptography firm Crypto AG sold equipment to governments and militaries around the world for decades after World War II. They were owned by the CIA:

But what none of its customers ever knew was that Crypto AG was secretly owned by the CIA in a highly classified partnership with West German intelligence. These spy agencies rigged the company’s devices so they could easily break the codes that countries used to send encrypted messages.

This isn’t really news. We have long known that Crypto AG was backdooring crypto equipment for the Americans. What is new is the formerly classified documents describing the details:

The decades-long arrangement, among the most closely guarded secrets of the Cold War, is laid bare in a classified, comprehensive CIA history of the operation obtained by The Washington Post and ZDF, a German public broadcaster, in a joint reporting project.

The account identifies the CIA officers who ran the program and the company executives entrusted to execute it. It traces the origin of the venture as well as the internal conflicts that nearly derailed it. It describes how the United States and its allies exploited other nations’ gullibility for years, taking their money and stealing their secrets.

The operation, known first by the code name “Thesaurus” and later “Rubicon,” ranks among the most audacious in CIA history.

EDITED TO ADD: More news articles. And a 1995 story on this. It’s not new news.

Companies that Scrape Your Email

[2020.02.12] Motherboard has a long article on apps—Edison, Slice, and Cleanfox—that spy on your email by scraping your screen, and then sell that information to others:

Some of the companies listed in the J.P. Morgan document sell data sourced from “personal inboxes,” the document adds. A spokesperson for J.P. Morgan Research, the part of the company that created the document, told Motherboard that the research “is intended for institutional clients.”

That document describes Edison as providing “consumer purchase metrics including brand loyalty, wallet share, purchase preferences, etc.” The document adds that the “source” of the data is the “Edison Email App.”

[…]

A dataset obtained by Motherboard shows what some of the information pulled from free email app users’ inboxes looks like. A spreadsheet containing data from Rakuten’s Slice, an app that scrapes a user’s inbox so they can better track packages or get their money back once a product goes down in price, contains the item that an app user bought from a specific brand, what they paid, and an unique identification code for each buyer.

A US Data Protection Agency

[2020.02.13] The United States is one of the few democracies without some formal data protection agency, and we need one. Senator Gillibrand just proposed creating one.

DNSSEC Keysigning Ceremony Postponed Because of Locked Safe

[2020.02.14] Interesting collision of real-world and Internet security:

The ceremony sees several trusted internet engineers (a minimum of three and up to seven) from across the world descend on one of two secure locations—one in El Segundo, California, just south of Los Angeles, and the other in Culpeper, Virginia—both in America, every three months.

Once in place, they run through a lengthy series of steps and checks to cryptographically sign the digital key pairs used to secure the internet’s root zone. (Here’s Cloudflare‘s in-depth explanation, and IANA’s PDF step-by-step guide.)

[…]

Only specific named people are allowed to take part in the ceremony, and they have to pass through several layers of security—including doors that can only be opened through fingerprint and retinal scans—before getting in the room where the ceremony takes place.

Staff open up two safes, each roughly one-metre across. One contains a hardware security module that contains the private portion of the KSK. The module is activated, allowing the KSK private key to sign keys, using smart cards assigned to the ceremony participants. These credentials are stored in deposit boxes and tamper-proof bags in the second safe. Each step is checked by everyone else, and the event is livestreamed. Once the ceremony is complete—which takes a few hours—all the pieces are separated, sealed, and put back in the safes inside the secure facility, and everyone leaves.

But during what was apparently a check on the system on Tuesday night—the day before the ceremony planned for 1300 PST (2100 UTC) Wednesday—IANA staff discovered that they couldn’t open one of the two safes. One of the locking mechanisms wouldn’t retract and so the safe stayed stubbornly shut.

As soon as they discovered the problem, everyone involved, including those who had flown in for the occasion, were told that the ceremony was being postponed. Thanks to the complexity of the problem—a jammed safe with critical and sensitive equipment inside—they were told it wasn’t going to be possible to hold the ceremony on the back-up date of Thursday, either.

Upcoming Speaking Engagements

[2020.02.14] This is a current list of where and when I am scheduled to speak:

- I’ll be at RSA Conference 2020 in San Francisco. On Wednesday, February 26, at 2:50 PM, I’ll be part of a panel on “How to Reduce Supply Chain Risk: Lessons from Efforts to Block Huawei.” On Thursday, February 27, at 9:20 AM, I’m giving a keynote on “Hacking Society.”

- I’m speaking at SecIT by Heise in Hannover, Germany on March 26, 2020.

The list is maintained on this page.

Since 1998, CRYPTO-GRAM has been a free monthly newsletter providing summaries, analyses, insights, and commentaries on security technology. To subscribe, or to read back issues, see Crypto-Gram’s web page.

You can also read these articles on my blog, Schneier on Security.

Please feel free to forward CRYPTO-GRAM, in whole or in part, to colleagues and friends who will find it valuable. Permission is also granted to reprint CRYPTO-GRAM, as long as it is reprinted in its entirety.

Bruce Schneier is an internationally renowned security technologist, called a security guru by the Economist. He is the author of over one dozen books—including his latest, Click Here to Kill Everybody—as well as hundreds of articles, essays, and academic papers. His newsletter and blog are read by over 250,000 people. Schneier is a fellow at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University; a Lecturer in Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School; a board member of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, AccessNow, and the Tor Project; and an advisory board member of EPIC and VerifiedVoting.org.

Copyright © 2020 by Bruce Schneier.